A Game of Thrones: The Lions Share

Lions, males in particular, have gripped the human race with fear, admiration, respect and misunderstanding for centuries. They are depicted as ruthless killers with an insatiable appetite for prey, and a blood lust for killing. They appear in many religious forms as symbols of power and strength, and are synonymous as symbols of status, wealth and social standing in cultures throughout the world.

Richard the Lionheart, Kind Richard I of England, who ruled from 1189 to 1199, was revered as a great soldier and brave crusader. The man eaters of Tsavo, probably the most notorious of wild lions, who were responsible for a number of human deaths in Tsavo, Kenya in 1898, were feared by hundreds of railway labourers. Revered or feared, lions have fascinated humans since the beginning of time and continue to do so today. So much of what we believe and know about lions is fed to us in sensational style with little fact or insight into what is real. For all these reasons, good and bad, lions have ultimately earned the title as the King of Beasts among wild animals.

This blog post came about as a result of the questions we are often asked about the two current dominant male lions on the Welgevonden Game Reserve and the interesting stories behind them. In writing this story, it was clear that a lot of information on lions needed to be clarified so that more of the fact could be brought to the fore without the glitter around the sensation.

Lions: Panthera leo in General

Lions are in no doubt the top predators in Africa, followed by leopard and spotted hyena. They are the largest of the African cats with males weighing between 180kg and 220kg, and females weighing between 130kg and 150kg. Males stand up to 1.25m at the shoulder. Once widespread throughout all of Africa into Asia and parts of Europe, there is probably no other species whose distributional range has shrunk over historical times to the extent as shown by the lion. They are now extinct in Europe, with the last specimen killed in AD100 in Greece. They persisted in Palestine until about the 12th century. The Asian lion is restricted to the Gir Peninsula in North-west India, with numbers reduced from 300 in 1953 to about 190 in a 1970 census. Through conservation efforts in India, they are now probably around 530 (2015). Lions are extinct in all other areas of Asia forming their original distribution.

In Africa, lions are extinct in the north and in many areas, poor records were kept of their shrinking numbers and ranges. In the Southern African sub-region, extensive records are kept of this change. Lions were once common in all of South Africa including near Cape Town until around 1860, but they have now been reduced to only occurring in reserves where they have been re- introduced. The last naturally occurring wild lion populations in South Africa are in the Kruger National Park and the Kgalagadi National Park. Combined in these two Reserves their numbers are around 2,500. Heavily persecuted by man, there are today fewer wild lions in the world than there are white rhino.

Being the most sociable of the big cats, lions live in prides ranging from 3 – 30 individuals. Pride size is dependent on the area and the typical prey they hunt. Prides typically consist of between 1 – 4 adult males, a number of adult females (one of which is dominant) sub-adults and cubs. Adult males are highly territorial and will spend much time defending their areas from stranger or rival males. They can spend 3 – 4 days away from the pride in doing so. Lions will take medium-sized prey, which is again dependent on the area and the pride size. They will hunt and kill every 3 – 4 days and may go longer in areas where food is sparser or during seasonal changes. A male lion requires about 5kg of meat daily and a female about 2.5 – 3kg daily to survive. There is no set breeding season, and adult females will give birth to 4 – 6 cubs after a gestation period of about 110 days. Cubs will suckle from any adult female lactating in the pride, and births are often coincidental within the pride to ensure maximum food availability for the cubs.

Of Kings And Queens

The lions of Welgevonden Game Reserve have a history like most royal families – filled with hope, change, toil and survival. In our lion blog post from September 2018, the current lions of Welgevonden were introduced to readers, giving a clear update on the current lion population on the reserve. From this story rose two new kings, and this is their story.

The Tembe male (above), king of the north, central, west and eastern areas of the reserve was born in February 2012. He was born into a lion population in Northern Natal at Tembe Elephant Park, hence his name. At the time of his introduction to Welgevonden Game Reserve, it was necessary for a young male of almost dominant age to be introduced to the reserve to assist rebuilding the lion population following the disease outbreak in late 2015. He was introduced in July 2016, and after only one day in the temporary housing boma, he broke out to start exploring his new home. He quickly took the park as his and became a great wanderer. He is now referred to as the Tembe male and is the dominant male in the Western Pride. He has fathered all the cubs born on the reserve since his introduction of which only one daughter of his remains in our current population. His royal blood line will not be carried forth in male offspring on the reserve yet, as the five sons he has fathered have since been relocated to other reserves to assist with the metapopulation genetic dynamics of lions in Southern Africa. The Tembe male is well-known for covering a lot of ground quickly and this is most likely due to the lack of other dominant males on the reserve and in the area. Welgevonden Game Reserve borders two other reserves, which have lion populations, Marakele National Park and a private reserve. He is easily recognised by his predominantly tawny mane with dark fringes closer to the neck and a short crew-cut hairstyle. He is a tall male, taller than his rival and has a long, narrow face.

The Dinokeng male (below), king of the south, was born in April 2010. He was born on Welgevonden Game Reserve but when he was approximately two years old, was relocated to the Dinokeng Game Reserve close to Pretoria. This was as part of a lion management programme introducing males into areas to mimic dispersion of males in natural lion populations. He was later returned to his home, Welgevonden Game Reserve, in February 2018. Having left when he was a young male, he was undoubtedly unsure of his new surroundings and made his way to the south of the reserve in what can only be described as homing instinct in lions. Dinokeng Game Reserve is relatively close to Welgevonden, about 100kms away. It was not until some months later, that Dinokeng and Tembe made contact and their territorial boundaries were laid down. Dinokeng dominates the south of the reserve with the Sterkstroom River valley forming the ‘official’ border, where Tembe dominates the northern, central and eastern areas. Dinokeng is recognised by being a larger, heavier set male with a thicker mane with more dark hair than tawny. He is not as tall as his rival and walks with a slight stoop. He has a distinct long, dark fringe.

It is both fascinating and humbling to watch these two kings fight for dominance both physically and intellectually. They constantly push each other to test the limits and are seen taking reconnaissance trips into their rivals’ territories from time to time. In what can only be typically ‘royal’ this Game of Thrones never ends.

Jessica and I were out on a late afternoon drive last year in November when such a saga was witnessed. We were in the central areas, deep in Tembe territory and having picked up on lion tracks, we were fervently searching for their owners. We narrowed their location down to a small section near Sekgwa Plains and eventually saw one of the Western Pride females on her own moving south, she was location calling and seemed anxious to find either her sister or the now 1.5 year old cubs of the pride. We lost her eventually as she headed into deep bush but decided to circle around to another area having picked up on male lion tracks, which we assumed must be Tembe, possibly with the other Western Pride female. We headed to an area where we knew they frequented and on rounding a corner came across the other said female with the male. Low and behold, this was Dinokeng not Tembe who we assumed was around! This was interesting, as we were certainly well out of the Dinokeng’s territory and here he was not only having stolen ground but was seducing a rival male’s female.

There are so many similar stories and more, of these rivals, which is best experienced in person.

Q&A – Our Lions Giving Perspective

We are asked many questions around lion behaviour. Answering these in respect to our male lions helps paint a clearer picture for this reserve.

- Do Male Lions Hunt?

In short, of course they do! Male lions hunt quite often. Male lions will typically leave their pride when they two years old, as the dominant male of the pride puts pressure on them to move on. Until they are around 5 – 6 years old, they will become nomadic or lodgers in other dominant male lion territories, avoiding trouble. During this period, they will need to hunt for themselves and will take any prey they can, often warthog or similar size animals that they can surprise or catch in an opportunistic situation. However, males continue to hunt into adulthood as they will need to eat even when with the pride. When patrolling territory, they will hunt for themselves as this can be 3 – 4 days at a time. Tembe in particular hunts wildebeest, ostrich and zebra quite successfully on his own.

- Why Do Lions Roar?

Lions roar for a number of reasons, and this only forms part of their communication ensemble. Males will typically roar to announce presence in that particular area of their territory. It also serves to warn any potential rivals in the area or within earshot that they are near and this area or territory is occupied or taken. Males will also roar to inform their prides that they are near, informing them that they have returned to the area. They will locate the females and pride by scent. A male lions roar is heard by other lions up to 8kms away. Humans can hear their roars from about 4kms away. Females will roar with males when they are with him, this is a sign of support to them and the pride dominance. Females will not usually roar outside of the males’ presence. On this reserve, I have not heard females respond to either of the males roaring. In saying that, I have been with Tembe before, where he roared a number of times and after an hour the Western Pride with their then 6-month old cubs came to join him. Tembe has a reputation of being a great wanderer and he covers huge ground. We are often asked why this is the case as in many other reserves. Male lions do not cover so much ground within their territories. We have discussed this at length and my theory on this reads; I believe male lions will roar expecting some kind of response. As a result of fewer rival males on the reserve, the Tembe male grew into a habit of investigating by foot whilst roaring, all the time expecting a response. In this way he discovered the reserve quickly and learnt the area well. The only response to his roars came from the rival males on neighbouring reserves, and so he continues to cover a lot of ground to ensure this remains the case. In other areas where there is a higher density of male lions, roaring receives a response in a shorter time and so less area is covered. I have yet to test this theory.

- Why Are Lions The “King of the Beasts”

This is a great question, and one that is not easily answered. There are many other species that could fit this role, but for some reason it is the lion who holds the reigning crown. Perhaps it was due to the fact that historically, as mentioned before, they were widespread in the old world and were the large predator in most areas.

I think the answer to this question is best answered by perhaps the oldest living race of people today, the San. In Laurens van der Posts book, The Heart of the Hunter; Dabe, his San aid on his return expedition to the Kalahari answered this question in true San style. I quote from this great read:

“Had I noticed he asked, how everything in life had a place of its own? For instance, the springbok had their pans, the eland and the hartebeest their great plains, the jackal and hyena, the lynx, the mongoose and the leopard each have a hole of his own, the lion though, could come and go and eat and sleep wherever he liked. Even the locusts had their grass and the ants their mounds of earth – and had I ever seen a bird without a nest?”

True to their great wandering behaviour, lions come and go as the please and hence deserve the title of king.

I remember as a child listening to a cassette tape over and over again on the calls of African wildlife and of course being captivated by the early morning call of a lion roaring. It has stuck with me for 35 years. “The dawn greeting of the king of beasts rings clear across grassland, woodland and vlei.” There is nothing quite like listening to the roar of a male lion on a dawn patrol of his territory. This precise picture is exactly what we think of when we think of Africa, and there is no place complete without the lion.

Much appreciation is expressed to Dr Jonathan Swart, resident Scientific Ecologist on Welgevonden Game Reserve for his input. Thank you to Andre Burger and Greg Canning for providing information on the births of the dominant males we currently have on the reserve.

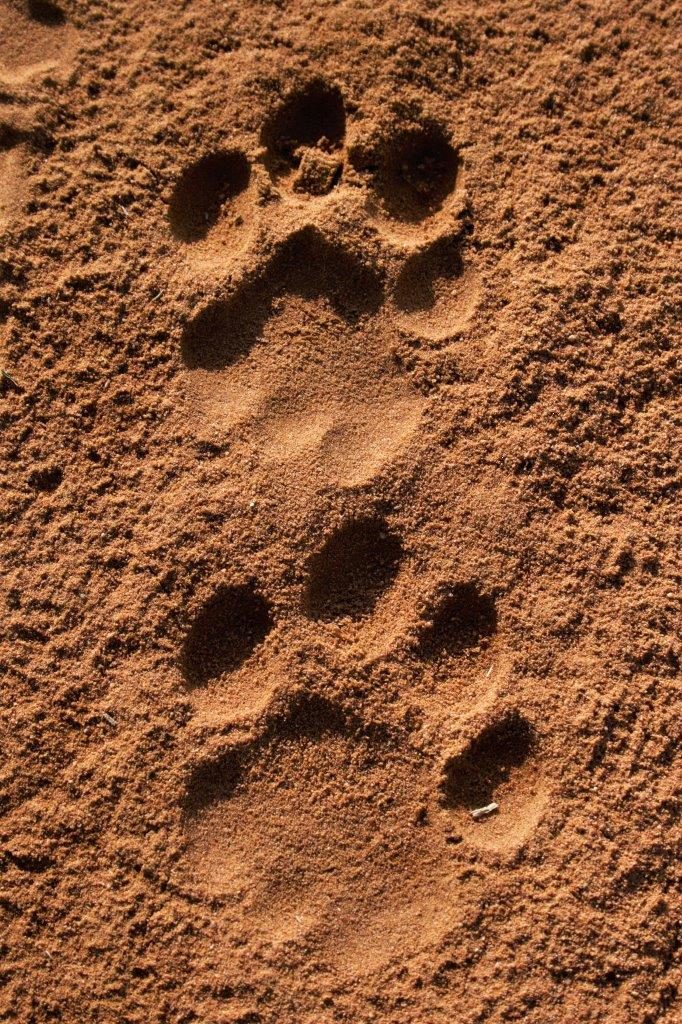

Picture note: Male lion tracks in the sand showing clearly the size difference between front (large) and back (smaller).

Words and images: Neil Davison

References:

- Personal observations by the author on Welgevonden Game Reserve

- The Behaviour Guide to African Mammals, Richard Despard Estes, Russel Friedman Books CC, 1995

- Mammals of the Southern African Sub Region, J.D Skinner & R.H.N. Smithers, Second Edition, University of Pretoria: Mammal Research Institute, Pretoria, 1990

- Field Guide to Mammals of Southern Africa, Chris & Tilde Stuart, Fourth Edition, Struik Nature, Cape Town, 2007