Beyond the Ball

Early morning, June 2017. We’ve aroused our guests to prepare for the morning game drive, when from down the valley comes a reverberating rumble. Startling all those lounging on the deck of the Indaba, the roaring sound penetrates the aroma of coffee brewing.

We look at each other. Lion! It is the Tembe Male, sprawled about two hundred meters up the ridge, south east of the camp. The excitement kicks in, and we’re eager to launch the game drive, which proves promising already. He roars again, only this time he is further away. We anxiously wait for the remaining guests to emerge and gulp down their morning brew before boarding the vehicles, feeling despair as he leaves the nearby valley, or so it seems. Our chance of finding him grows slimmer with every passing minute.

Fifteen minutes later, he roars again. He’s coming closer. A small wave of relief fills us – he is coming back. This seems to be odd behaviour but perhaps he is looking for something, or he’s on the scent of a female or perhaps a kill. Nonetheless, his motives or indecisive wandering phase us little. He’s around and that is all that concerns us.

The engines start and we move away from camp, progressing slowly to where we last heard him. We find him! He’s lying on a small ridge some twenty meters from the road, sitting next to his kill from the night before. It’s an unfortunate Wildebeest bull, whom we’ve seen every night for the past six months resting in the tree line behind the waterhole. His eyes reflect torchlight as we safely navigate our guests back to their rooms every night, but are now extinguished forever.

The lion roars again, turning towards the southern ridge. His voice sounds distant as his call echoes off the hills and reverberates down the valley. What we had assumed was him moving away was, in fact, him simply turning away from us, shifting his position to better promote his presence and declare his territory.

We watch him for some time, waiting for him to move, which he ultimately does. He gets up and walks the well-worn game path, to quench his thirst at the camp waterhole, before making his way back to his meal. He finds a flat, comfortable spot under a Horn pod and calls it a day, although the day has just begun.

With all the excitement building to the eventual sighting of arguably the most iconic African mammal species and royal member of the proverbial Big Five, there is much that has been overshadowed and lost to sight. Whilst sitting with Tembe, only the occasional flick of his tail to betray his resting spot, a group of broken balls lie scattered some 3 meters from where we have stopped. Slowly and quietly, sliding out of the seat, I retrieve the remnants of a ‘family tree’ and return to describe this fascinating find to the guests. This is the story I want to tell, with the presence of the majestic Male lion paling to insignificance.

We are more often than not too preoccupied with what we believe we should be looking for, that we fail to see the very golden nuggets right under our noses. These go undetected in a mental blind spot that we have no inclination even exists. We talk of the small things, but these are quite fundamentally just as large as the big things. This blog has been rolling around in me ever since.

Insects are by far the most numerous species of animals on Earth, with over 1.5 million known species. Beetles make up the largest portion of this with their Order: Coleoptera, comprising more than 300,000 species worldwide with around 18,000 species in Southern Africa. Beetles make up 75% of all living animals known to Man and thus, makes them by far the largest order in the entire Animal Kingdom.

They are found in a variety of shapes, sizes and colours and occupy almost every conceivable environment with as many behaviours, preferences, and adaptations. From the fast-moving Ground and Tiger Beetles or CARABOID Beetles, to the beautifully ornate Jewel or BUPRESTOID Beetles and the industrious Dung Beetles or SCARABAEOID Beetles, they are easily recognised for their hard, outer casings and a distinguishable overall appearance.

The dung beetle has captured the attention of man for thousands of years. Belonging to the sub-family Sacarabaeinae which forms part of the super-family Scarabaeidae (often referred to as just ‘scarab beetles’), the dung beetles share many similar traits to their other beetle counterparts within the Order, however their distinct behaviour and preference for manure sets them apart. For the most part, dung beetles, as with most insects, go unnoticed, and had it not been for the ball-rolling varieties, we probably would have given this unique group of critters little attention. Going ‘Beyond the Ball’, we start to understand more of what, why and how these creatures go about shaping their own lives and impacting those who share their ecosystems.

Let us roll this story back a bit.

There is much that we do know about dung beetles as they have been observed and researched for thousands of years.

7000 years ago, the Egyptians held the small ball-rolling sub-family of dung beetles in high regard. The manner in which they rolled a neat symmetrical ball of dung and buried it, to later re-emerge, was captivating. This behaviour was perceived as a powerful symbol of resurrection, and signified the creative power of the Sun. For the Egyptians, this held great relevance in their belief of the afterlife, and hence the dead were buried with food and wealth that would carry them to the life hereafter.

The Egyptian god Khepri was depicted as the form of a man with the head of a scarab beetle. He was associated with creation and becoming. He gave life. It was believed that he would roll the Sun across the sky to the end of the day, to its death, only to re-emerge at dawn to repeat the process. And so the icon of regeneration and rebirth was relevant, as it was symbolised in the behaviour of the dung beetles. This affirmed the belief that death was not the end of life. Ball-rolling dung beetles use their back legs to roll their balls along, which in itself signifies the reversal of life, a rebirth or regeneration.

These beetles adorned the Egyptians in life and death and were represented in beautiful, ornate jewellery. These beetle-depicting amulets were worn by the living, protecting them from the evil in life, and those decorating the inside of final resting chambers ensured resurrection and a passage into the afterlife. This amulet was found amongst the belongings that were buried with the great Egyptian Pharaoh, Tutankhamun, who was the last of the Great Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt at the end of the 18th Dynasty.

The beetle was fundamental to their beliefs and featured in all daily Egyptian life. In the Heavens above, the scarab was depicted in the stars, later to be metamorphosed by the Greeks and Romans to depict a crab, which forms the zodiac we today recognise as ‘Cancer’. The dung beetle species, Scarabeaus sacer – the Sacred dung beetle, depicted in Egyptian culture since before 4000BC – still scurries along its daily life path to this day.

Beetles appeared on Earth about 285 million years ago, with the dung beetles making their appearance about 65 million years ago. They have certainly had sufficient time to perfect their art of dung-moving.

A research article published in 2016 questioned whether the change in dinosaur diet during the Cretaceous period (145 – 65 million years ago) may well have been the significant time that gave rise to the dung beetles. It was long debated amongst scientists whether the dung beetles arose in adaptation to dinosaur or mammalian dung. Beetles, as we know today, have diets that are herbivorous and non-herbivorous. The evolutionary success of beetles, and other terrestrial insects, is often attributed to the co-radiation with flowering plants, or angiosperms.

The super-family of beetles that the dung beetles belong to includes both the herbivorous and non-herbivorous species. Molecular research shows that the dung beetles may well have risen around the middle of the Cretaceous period, more likely with dinosaur dung than mammalian. However, this also coincides with the arrival of the flowering plants. Mammals first arose about 215 million years ago. However, much later and well after the extinction of the dinosaurs – around 10 million years ago – the number of mammal species exploded. This means that the few species of smaller mammals that were around during the dinosaur period, when the dung beetles arose, could have had little influence on the behavioural emergence of the dung beetles. It is therefore speculated that it was the shift in dinosaur diet to a more nutritious, less fibrous diet of flowering plants that provided a more palatable dung source for the beetles, leading to this niche diversification. This quite likely gave rise to the beetles who chose to dwell in the manure of large herbivores.

Dung beetles today are most recognised by their coprophagus habits – feeding off the dung or manure of mostly, but not exclusively, large herbivores. They are found on every continent, except Antarctica, with their miniscule brains capable of deciphering aromatic and visual stimuli that the advanced human brain cannot comprehend. Of the 18,000 known species of beetles in southern Africa, about 800 species of dung beetles occur. They are broken down into four distinct groups, with varied behaviours to satisfy their feeding and breeding needs.

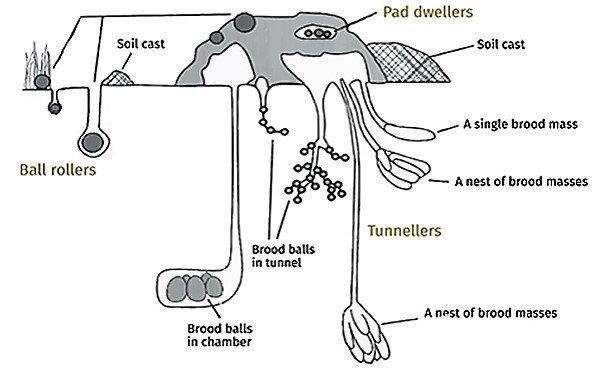

The Endocoprids, also known as the ‘dwellers’ who spend their time inside the dung heap where they feed and breed quite easily, but under conditions of high competition.

The Paracoprids, also referred to as the ‘tunnelers’ who will roll irregular balls of dung and bury them in tunnels directly beneath the dung heap. Each tunnel can contain a number of these balls, which are used for breeding. The beetles commute between the dung and soil interface to their underground nests and are rarely seen.

The Telecoprids, the infamous ball-rolling dung beetles, who produce neat, symmetrical balls that they roll away from the overcrowded dung heap. They use their dung ball to woo a female and create a breeding vessel to pass on their genetic legacy.

Lastly, the Kleptocoprids, the thieves of the dung beetle realm who wait for the work to be completed before hijacking the balls made by others and making off with it to continue their own breeding process.

The greatest number of dung beetle species is found around the tropics, with their numbers steadily declining as one moves further towards the poles. This is likely attributed to the amount of food available at the tropics for suitable herbivores that provide the dung for the beetles to exploit. Itis also most likely due to the soil suitability for burying the dung balls in these wetter, tropical environments. The ball-rollers make up a small portion of the overall dung beetle diversity, with only 10% of the known species attributed to this group.

The emergence of ball-rolling is likely in response to competition in the dung heap for space, food, and enticing potential mates. Within minutes of fresh dung being deposited by a large herbivore, the dung heap is inundated with beetles, processing it into a renewable resource.

Let us return to the broken balls that we found that June morning.

Dung beetles use the dung ball to feed and attract a female, and therefore to breed. As we see in the diagram of the various nest preferences for these beetles, the size, shape, and type of ball differs. This variation is clear in the image showing the different size of balls, where the larger ball was rolled away and buried by a species of ball-rolling dung beetle, whilst the smaller balls were rolled and buried inside the dung heap from which they were made (White Rhino).

The broken balls discovered that June winter morning were from a species that rolls their ball away from the heap to breed. The male beetle rolls a ball of dung from freshly deposited material, in the hope to attract a female. He will roll his ball to a predetermined spot, bury it, and then begin the process of wooing a female, using pheromones that he releases at the entrance to his tunnel where the ball is buried. Once a female has been enticed and her choice made, she joins the male with his dung ball. They spend time together, feeding on the ball and mating in a sort of honeymoon ceremony. This can take a day or 2 and once they emerge from this coital underground getaway, they begin the process of creating what is referred to as a ‘brood ball’. They will locate fresh suitable dung, create a sizeable ball together and roll it away, again to a predetermined spot. Adults of some species can bury dung equivalent to 250 times their body weight in a single day.

The male performs most of the rolling duties, whilst the female makes the brood ball tidy and prepares it for the egg laying. The ball is prepared by both male and female, the top end folded back to create a cavity in which the female will lay a single egg. The edges are then folded in to secure the egg in the ball of dung. The ball is caked in a layer of soil, where it is then left in its chamber for the young to develop. The egg sits surrounded by dung until ready to hatch, at which point the dung beetle larva emerges.

As with most animals, the dung beetles need nitrogen in their diet, drawing them to the dung heaps. Nitrogen is important in an animal’s diet for protein and muscle development. The cells from the gut lining of the host herbivore deposited in the dung are a protein-rich source of nitrogen which the adult dung beetles seek. The dung itself also provides a nutrient-rich source of moisture. The adult beetles cannot eat the fibrous matter in the dung as they lack the mouthparts for chewing and the necessary gut microbes to assist in breaking down the cellulose-rich plant matter. An adult can eat up to 24 times its own body weight of dung in a single day!

Unlike the adults, the larvae are better suited to consuming this cellulose-rich diet. They possess chewing mouthparts to break down the course plant material in the dung, and the gut microbes necessary to convert the cellulose into sugars and aid in fixing nitrogen. The gut microbes could be obtained from the dung itself which is present in the host herbivore’s gut system. Whilst eating the dung in which they are also living, the larvae create a smooth inner cavity.

At this stage of their life cycle, the larvae prepare to pupate and develop into an adult. In some species, the larvae use their faeces to create a cement-hard cocoon in which they will develop into an adult. Once there is sufficient rain and moisture and the development of the pupa has completed, the adult beetle will emerge from its underground chamber, leaving its early life pod buried forever. The overall life cycle of the dung beetle from egg to adult can take between 28 days to 3 months, depending on the species. Some species give life to more than 1 generation in a season. The image showing the inner cavity of the brood ball shows an undeveloped pupa still inside.

A different nest that I discovered had three brood balls dug out of the ground (not by me) of which one of the brood balls (Left) had a distinct hole. It was clear that from this brood ball, an adult developed beetle had emerged from its chamber. The middle ball was intact and empty and likely the egg had never developed into a larva It was either unfertilised or did not incubate. The last brood ball (Right) was still intact and had a dead, undeveloped pupa still inside.

As an adult, a dung beetle can live up to 3 years. During the winter periods they are inactive and remain dormant until sufficient summer rains have fallen, drawing them out of their diapause – a period of physiologically-induced dormancy between periods of activity.

So once the life cycle of the beetle is complete, and the balls remain hidden buried, how is it that they become exposed above ground? As with the nest that we found whilst with the male lion – remember him – most nests that are compromised are the result of honey badger activity.

This crafty, versatile mammal can locate, sniff out and excavate the brood balls of dung beetles, to gain access to the large juicy larva. This nitrogen and protein rich snack is simply too tempting to leave buried. I have located at least 12 nest sites dug up by Honey Badgers on this reserve alone. Many more will succumb.

Did you know?

Rolling around in dung all day has its challenges, yet nature provides a solution. Sitting hidden in the joints of the dung beetle’s outer armour layer are little mites who help to keep the joints of his exoskeleton clean. These mites do not eat the dung itself, but once a dung beetle settles on a dung heap to get busy, the mites eat the eggs laid in the dung heap by flies. This not only provides them a meal whilst moving about between dung heaps on their armoured transportation, but controls the number of flies often associated with dung and waste.

Did you know?

In the De Hoop Nature Reserve, a fynbos reserve in the Western Cape, a type of plant species (Restio) has adapted its seeds to resemble that of the dung pellet of a large herbivore, the Eland and the Bontebok. The dung beetle, fooled to believe the seed is a dung pellet, will roll it away and bury it, only to find that it cannot be eaten nor can it host an egg inside it. Further to appearance, the seed emits a dung-like odour to complete the act. This has no adverse effect on the beetle, as once it realises the pellet is not what it seems, it simply leaves it and goes in search of more suitable dung material. Large seeds such as these are difficult to be buried naturally and require mechanical intervention to aid seed imbibition and development.

In fynbos environments, where the herbivore numbers are low due to the low-quality plant food available, this type of deception is easier to get away with. The beetles are drawn to dung and the seeds provide a perception of abundance which is otherwise in limited supply. In Savanna ecosystems this type of deception is not prevalent as there is an abundance of large herbivores and, naturally, their dung.

Did you know?

A species of near-endemic dung beetles in southern Africa, belonging to the sub-genus Sceliages, have moved away from dung and have developed predatory behaviour. Renouncing their inherent coprophagous habits, the physiological adaptations they have undergone allow them to predate on certain groups of millipedes.

Their middle legs have adapted to grasp their prey, and they use their modified mouthparts to pry open the ring segments of the millipede. They use the chitin (exoskeleton) and the viscera (internal organs) of the millipedes to roll into brood balls. A single egg is laid inside the brood ball, which is watched over by the female – a unique and rare behaviour in insects.

Did you know?

In the Addo Elephant National Park in the Eastern Cape, an endemic species of flightless dung beetle exists. The abundance of large herbivores in this reserve, such as elephant and buffalo, may have aided in this flightless beetle evolving. The need to fly has been lost, possibly due to:

- Large beetle body size

- The lack of necessity to fly to locate dung heaps, due to dung abundance

- Their low fecundity – this beetle species only has one offspring in a breeding season, with the female showing maternal care to the egg

Dung beetles are undoubtedly fascinating and deserve the attention they have drawn for thousands of years. The Batonka’s story from Angola tells of the dung beetle who is not vain but uses her strength to distribute resources, using the dung to protect her children and hide them from predators, whilst competing for recognition in the animal kingdom with the beautiful butterfly. This tells a valuable life story to us all.

The beetle who longed for golden shoes in Hans Christiaan Anderson’s story from 1861 reminds the reader of our world where we often covet that which others have without realising our own fortunes in the things we are surrounded by.

For insight into nocturnal dung beetles that navigate at night using solar radiation from the Milky Way, or how dung beetles use their dung balls to thermoregulate, or a dung beetle in South America who rolls dung with his front legs, the recently published book “Dance of the Dung Beetles” by Marcus Byrne of the University of the Witwatersrand gives great insight into this little insect’s life on earth and everything that, for the most part, unknowingly revolves around it.

A must read for any amateur or avid entomology geek.

Text – Neil Davison

Photographs – Neil Davison

Image of Amulet – Pinterest

References:

- 30 years of personal observations by the author on various Reserves in South Africa including Welgevonden Game Reserve

- Dance of the Dung Beetle, M. Byrne & H. Lunn, Wits University Press, Johannesburg, 2019

- Field Guide to Insects of South Africa, M. Picker, C. Griffiths, A. Weaving, Struik Publishers, Cape Town, 2002

- Southern African Insects & their World, A. Weaving, Struik Publishers, Cape Town, 2000

- The Invertebrata: 3rd Edition, L.A. Borradaile, F.A. Potts, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1958

- Two dung beetle species that disperse mimetic seeds both feed on eland dung, Midgley JJ, White JDM., S Afr J Sci. 2016;112(7/8), Art. #2016-0114, 3 pages.

- If Dung Beetles (Scarabaeidae: Scarabaeinae) Arose in Association with Dinosaurs, Did they Also Suffer a Mass Extinction at the K-Pg Boundary, N.L. Gunter NL, Weir TA, Slipinksi A, Bocak L, Cameron SL, 2016, PLoS ONE 11(5): e0153570. http://doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153570

- The African Beetle who went on his travels, Hans Christian Anderson, 1861 http://hca.gilead.org.il/beetle.html