Giant Bullfrog

There is a little water pan on the Reserve. For the most part it goes unnoticed, lying dry as a bone in the African sun. A small depression of dust and sand littered with the heavy footprints of bovids who in days past plodded through it, in the hope of bringing some relief to their parched throats.

Its October, the dark clouds begin to gather. The first signs of summer rains begin to excite the inhabitants of the Reserve. The little pan lies still in anticipation. Staring up at the promise of rain, its surface reflecting nothing of the season before.

It rains, actually it pours. Small silver rivulets snake their way to the pans belly, gathering in a great mass of brown lifegiving liquid. The pan fills, and with it so to do the hopes of many creatures who rely on it through the Summer.

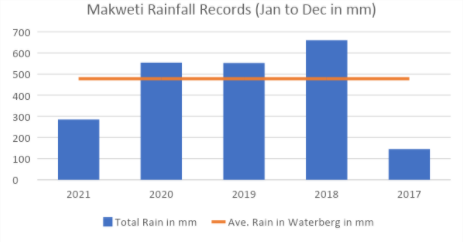

South Africa’s average annual rainfall is 490mm. There are however areas that receive much more than this and those that receive considerably less. The Waterberg, where the Welgevonden Game Reserve is located, receives on average of 478mm or about 19 inches per annum.

In many arid regions, pans form a critical water source that support local communities, livestock, and wildlife, with readily available water resources (3). However, these waterbodies are often unevenly distributed across the landscape and highly ephemeral, influencing their ability to provide water especially in water scarce areas.

This little pan is an important water source for the area of the Reserve in which it is located. Throughout the summer, many birds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals make use of it to fulfil their daily requirements.

‘The Hour has come!’ said the Badger with great solemnity.

‘What hour?’ asked the Rat uneasily, glancing at the clock on the mantelpiece.

‘WHOSE hour, you should rather say,’ replied the Badger. ‘Why, Toad’s hour! The hour of the Toad!’

This is Bullfrog Pan.

One such species who relies on our little pan is the Giant Bullfrog, who uses it as an important breeding arena, when times are favourable.

The Giant Bullfrog Pyxicephalus adspersus is the largest Anuran (the group of tailless amphibians known as toads and frogs) in southern Africa. Males can reach up to 1 kg weight, typically they are around 400-900g, and can reach lengths of 240mm, from snout to vent (where their tail would be).

Easily recognisable for its large size and dark green olive colour, it is a well-known species of frog respected for its aggression and tendency to bite, in defence. Their preferred habitat is mainly grassland and open Savanna, where shallow grassy pans, vleis and other rain filled depressions occur seasonally. These pans serve as ideal breeding grounds for them to spawn. Adults live in burrows that range from a couple of hundred meters to over a kilometre from water pans. Burrows can be up to one meter deep in sandy soils, their preferred substrate, to about 30cm in more clay soils. Reverse sexual dimorphism in the species, means the males are considerably larger than the females; females varying in weight from 80 – 300g.

Males are territorial and have a high fidelity towards their spawning pans, and to their long-term burrows. Foraging for food at night, Bullfrogs feed up to 300m from their burrows in search of insects, other frogs, lizards, snakes, rodents, and birds. Males in particular are nocturnal foragers reducing their risk of desiccation and vulnerability to predation (by birds and mammals). Young Bullfrogs feed voraciously and will cannibalise their siblings. Post metamorphosis the juveniles grow rapidly increasing in size by up to 1000% in only nine months.

Rainfall is critical for Bullfrog breeding. Suitable breeding conditions occur in November usually, however if conditions are favourable with sufficient rain falling, Bullfrogs will emerge from their burrows earlier. Rainfall events in excess of 60mm or 2.5 inches in a short time period, trigger the emergence of the adult breeding Bullfrogs. If during the summer, conditions are favourable again, a second breeding window can occur, usually in January or February.

Individuals spend most of the year in a state of torpor buried underground in their burrows. Torpor is an involuntary physiological state where the body enters a state of dormancy as a result of the lack of food availability. In this state the physiological activity of the frog is brought on by reduced body temperature and metabolism. This is how they spend the majority of time outside of the breeding season, during Winter, and during extremely dry Summers. Hibernation in contrast to torpor is a voluntary survival tactic which animals living in harsh winter environments adopt to survive until the next summer season. Bears are a common example of hibernators.

In preparing for this dormant state, the Bullfrog will shed layers of skin which create a cocoon casing around them. This protects them from desiccation primarily, reducing evaporated water loss through the skin by 50%. Further to this, their torpor state slows their metabolism down, reducing Oxygen consumption by as much as 75%. They will spend six to eight months in torpor during the year, sometimes remaining in this state through summer where the rainfall is insufficient to emerge and breed. This is known as Aestivation, where a state of dormancy occurs in summer as opposed to winter in the case of hibernation. Aestivation is evident in species of reptiles and amphibians living in arid conditions and extreme heat. This is a ‘light’ state of dormancy that allows for the rapid reversal to normality should conditions quickly become favourable.

Bullfrogs can live up to forty years of age, although typically most adults will live to twenty years or thereabouts. This is a good thing, if one has to skip breeding seasons due to drought and other limiting environmental conditions.

On emerging after good rains, males will congregate at spawning pans where they fight aggressively for territory. Larger males will hold more favourable breeding territories, attracting more females. Medium size males will jostle for position within the territorial males’ territory with the hope of snatching up suitable females. The smaller males or satellite males, watch the fracas between the larger males, waiting to subdue any unnoticed females on the pans’ periphery.

Adult females prefer the larger territorial males for breeding, and on entering his territory or pan, will move slowly, submerged to eye level, towards the territorial male. He will in turn quickly bond with her in amplexus, where she is completely covered by his massive body. They will remain in amplexus for a couple of minutes to a half an hour. During amplexus, the female stretches her legs, raising her vent (‘tail’) and releases her eggs (1000 to 6000 eggs) whilst the male fertilises them. This is done in mid-air, outside of the water to ensure better fertilisation. The eggs are then deposited in small bundles in the grassy shallows, along with those of other females. Females will be involved in only one to three spawning events, the energy requirements to produce ova restricting their seasonal breeding prowess. Males are active at many spawning events, in order to increase their breeding success. What is interesting is that female burrows are a lot further from breeding sites than those of the males. This is possibly due to them travelling less frequently and attending fewer spawning events.

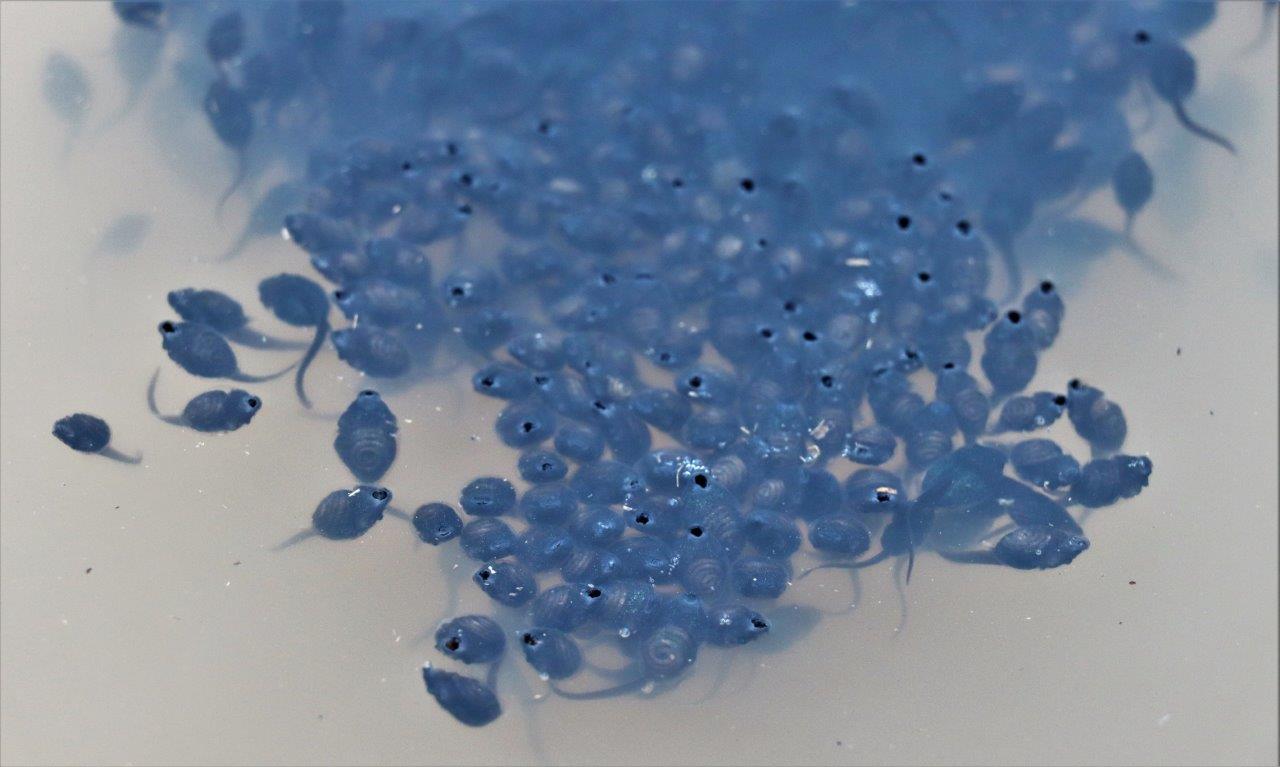

The Tadpoles develop within thirty-six hours of the eggs being laid and congregate in massive schools in the pan shallows. It takes eighteen to thirty-three days for metamorphosis to complete the tadpoles’ development into a froglet. Development timing is dependent on water temperature and food availability (tadpoles feed typically on plants, algae, and tiny insects). Territorial males assume a parental role and aggressively defend the developing tadpoles prior to metamorphosis. Where pools begin to shrink, he will protect them from desiccation, creating channels between pools that the tadpoles can traverse in order to get to deeper water.

Tadpoles have gills which enable them to breath, but most also develop lungs. They are seen frequently surfacing for air. Large tadpoles breach the water surface taking in air, where smaller tadpoles suck at the water surface, trapping a bubble of air from which they breath. In pools of water where oxygen levels are low or in shrinking pools, this is commonly seen.

The waterhole at the Camp is a hive of activity throughout the year, but peaks during the summer months. A variety of frogs and toads gather to use it meet and breed. At night we are often swooned to the delightful calls of many species such as the Bubbling Kassinas, Red Toads, Plain Grass Frogs and Cacos. The little lily pond in the Main Lodge also attracts the beautiful shy white ghost-like Foam Nest Frog, inconspicuously tucked on a rock.

The Red Toads are numerous and gather at night on the pathways close to the lights, foraging for insects drawn to the glow. They breed in the pools of water that gather in the gorge under the bridge and make use of the waterhole at the Indaba for their young to develop. During heavy rain patches, the tadpoles venture out of the waterhole into the pools collecting around it to forage for food, only to be drawn back to the safety of the waterhole when these temporary quick drying pools recede. Tadpole mortality is high and given their abundance they form a vital food source in the chain.

Toad is in Trouble!

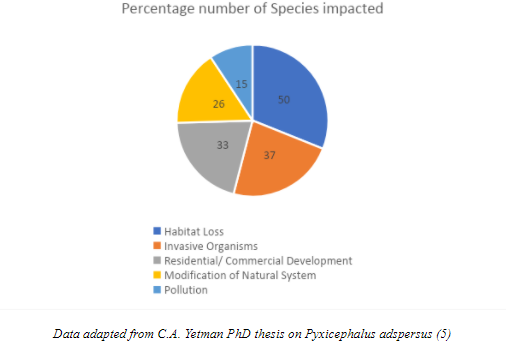

In South Africa, the Frog diversity is great and boasts some 117 species, of which 43% of them are endemic. Sadly, close to 17% (20 species) are globally threatened, facing many challenges to survive. Major threats to these critical ecosystem constituents are highlighted.

Almost one third of all known Amphibian species globally (including frogs and toads) are regarded as threatened and in a steady decline. They are regarded as the most threatened of the five vertebrate classes (Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Mammals, Fish). The outlook is believed to be more distressing, as more than 25% of Amphibians are termed data deficient, which means there are no reliable records of numbers, diversity, demographics, or distribution.

In certain populations, harvesting for commercial consumption is a considerable threat. In Swaziland, the Giant Bullfrog has become extinct, as a result of over harvesting for food. In Namibia, the Giant Bullfrog population faces a similar fate where they, locally known as efuma, are regarded as a delicacy and harvested for human consumption.

The largest Anuran in the world is the Goliath Slippery Frog, Conraua goliath. They are found in Gabon and other parts of Equatorial Africa, where they are harvested for food and for the pet trade. They weigh up to 3kg (just over 7 pounds). They face steady decline and are regarded as ‘Endangered’.

The Giant Bullfrog is listed as ‘near Threatened’ on the IUCN Red Data List of Threatened Species. Their numbers are registered as declining. The largest South African population, in diversity and numbers, is located in the Gauteng Province, where the population has declined by more than 90% since the 1970’s. Throughout South Africa the picture is equally distressing – the population has decreased from 50 to 80%.

So as in Kenneth Grahame’s, the Wind in the Willows where Toad must put up with the antics of Rat and Mole, so too does our ‘Toad’ have to contend with a changing environment with devastating consequences.

Text – Neil Davison

Photographs – Neil Davison

References:

- 30 years of personal observations by the author on various Reserves in South Africa including Welgevonden Game Reserve

- Louis du Preez, Vincent Carruthers, A Complete Guide to the Frogs of Southern Africa, Struik Nature, Cape Town, 2009

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group. 2013. Pyxicephalus adspersus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T58535A3070700. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T58535A3070700.en

- Kenneth Grahame, Wind in the Willows, Penguin Books, London, 2005

- Chantel Chiloane, Timothy Dube, Cletah Shoko, Monitoring and assessment of the seasonal and inter-annual pan inundation dynamics in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Southern Africa, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, Volumes 118–119, 2020, pg. 102905.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2020.102905

- Caroline A, Yetman, Conservation biology of the Giant Bullfrog, Pyxicephalus adspersus. PhD thesis

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281202370

http://www.conservancies.org/Downloads/Giant%20Bullfrog.pdf