The Baboon, A Poet And A Naturalist

Change is inevitable. Be it good or bad, it is bound to happen. Most of what changes is not so much about what has changed or is busy changing, but more one’s perception of what is different. Many things change around us without us knowing. Many changes have different impacts or effects on us or the environment or the world. Think about what has changed in your life over the past five months. We can no doubt all feel or see the change that has occurred the world over, yet this one change has triggered a snowball of adjustments. This has many different meanings to us all.

Climate change.

So, is it the perception of change or our understanding of change that is more important? We are often asked about climate change in South Africa and more so how this has affected or changed the environment on the reserve. Do the animals change as a result? Can we see the change?

Climate change has been happening around us for years and only now that we see what we believe to be a sudden change that we never saw before, do we have the realisation that it is real. It always has been. Just because now it is more drastic, and maybe a little too close to home do we behave in a manner that reacts to the change taking place.

Watching news reports recently amid the current worldwide change, we are enamoured by our local wildlife exploring cities and other urban areas. This change in behaviour is interesting and well, something we can more easily see than explain. We see it here, on the reserve right in camp too.

A Few Changes We’ve Seen Around Us

Squirrels

There have always been very few tree squirrels on the reserve, and in the last four years, we have slowly seen them coming back. There are a few individuals we have seen in the ‘kloof’ leading down to Makweti Safari Lodge, and recently we have seen them around the house. We rarely saw them in camp, but over the past four weeks, we have seen a pair of them on a daily basis. Perhaps they are adapting to the quiet of the camp without guests and staff around. As they habituate to us being around as the only human interaction, they will settle and be frequent visitors in camp.

Cicadas

Cicadas, the small noisy insects more often heard than seen, have also come back into camp. This family of insects belonging to the order Hemiptera was not heard here for quite some time. In fact, we cannot remember when last we heard them. Now, almost every day (especially on warmer days) they call their very distinct and iconic bush sound. The call is a monotonous ringing noise they create by vibrating their tymbal muscles. The tymbals are ribbed membranes at the base of the abdomen. They call to each other to attract a mate, but also to repel birds.

Birds

This would make sense, as we have noticed an increase in bird species in and around camp too. Orioles, bush shrikes, woodpeckers, greenbuls, and bulbuls are all frequently seen. We have seen a pair of African hawk eagles and black eagles. Walking to room one and two this week to inspect the camp, we noticed there are new little dassie pups in the colony. We watched as the mothers attentively watched us and their little ones, not at all concerned by our presence. With a sudden start and high pitched ‘yelp’ they dashed off and ran under the closest rocks. We knew something had changed, and there it was a juvenile African hawk eagle soaring about 15 meters above, on the hunt.

Baboons

With only the three of us in camp the past seven weeks, we have begun noticing more patterns in the animals that come close to and inside the camp. The kudu are regulars at the waterhole, as are the zebra, warthog, klipspringer, and impala. Baboons make their way down from the ridge above the staff housing daily, moving slowly in the warm afternoon sun, grooming, and feeding their way down the valley to roost for the night. This has never been a regular occurrence and in the past, they would do this maybe once a month.

Adapting To Change

These behavioural changes are fascinating in animals and are driven by time, the ability to learn, and the response required to adapt to the changes. Given a chance, I believe most animals would adapt to changes in their environments more easily over time. Sadly, changes brought about by human influence are too frequent and too limiting for them to adapt to quickly enough, and this leads to their demise or them leaving an area.

Chacma Baboons, as we have seen, are resilient, resourceful, yet crafty vagabonds of the bushveld. They have the ability to adapt more so than most other species, and being primates, they are gifted with the ability to learn. Heading to the bustling metropolis of Vaalwater on a Wednesday for our usual grocery run, we have noticed the same flange of baboons outside the reserve, grooming, feeding, and socialising in the early morning sun. They roost somewhere along the river that flanks this section of road into town, as they are always heading into the ridge on the south side of the road. The youngsters play and jostle in the road and are incredibly entertaining.

Understanding animal behaviour has become more fascinating to scientists and conservationists over the past century. Understanding animal behaviour has made us more aware of the plight of many species and taught us how to use different species as indicators of the changes in the environment.

The study of animal behaviour or Ethology is attributed to a well-known South African character who is dubbed the ‘Father of Ethology’ who spent much of his time right here in the Waterberg where his interests bloomed.

The Poet And A Naturalist

Eugene Nielen Marais, born 9th January 1871 on the farm Les Marais, Daspoort, north of Pretoria, was the thirteenth child in his family. He spent his childhood in Pretoria and the Orange Free State where he resided with his older brother Charles before attending school in Paarl, Western Cape. He later went on to study law in Britain, completing his degree in September 1901, where he was eager to return to South Africa, as the Anglo Boer war was ending.

It would be the tragedy of losing his wife and son shortly after his son’s birth in 1895, which led him into the Waterberg in 1905. This would fuel his fascination of the environment around him.

At the time that Eugene Marais first entered the Waterberg, it was known to him only as a mystery place from his boyhood. He wrote; ‘From that wonderland, the hunter’s wagons used to come to Pretoria to unload their ivory and skins and the trading stores, giraffe-skin whips, sjamboks of rhinoceros and hippopotamus hide, rhinoceros horn and dried hides of all the big animals of the wild bushveld… and often live animals came with the wagons: small zebras, eland, ostriches and monkeys, and in rude cages birds of wonderful plumages’.

His travels whilst studying law had always led Marais to question and ponder the intricacies of life and although he had no training in biological science, his interest was to become pioneering work.

On visiting the Waterberg, he became interested in the social order of termites, which he later described, that as a living colony, should be referred to as a super-organism where each termite plays its part like the cells of the body. His other interest was the social behaviours of the baboons he found in the ‘bobbejaankloof’. Both studies would become some of his greatest works. The Soul of the White Ant published in Afrikaans media in 1925, and The Soul of the Ape, published posthumously in 1969 became popular readings in South African literature and both are great reads.

His fascination, which led to the observations of both these interests was to become the cornerstone of what we know today as the study of animal behaviour, now referred to as ethology. Incidentally, the term ‘ape’ although incorrect in its application to baboons who are regarded as primates, is a play on the translation of Marias works from the Afrikaans word for them. The word ‘aap’ in Afrikaans is used for apes and primates and translates to ‘ape’ in English.

Much has been written about Eugene Marais, for his pioneering work in animal behavioural studies, his poetry, and the tragic life he led and suffered. In researching this article, I did not want to rehash all the information already written about him and his life, but in particular, I wanted to find evidence of him spending time in the areas that are today incorporated into the Welgevonden Game Reserve.

Within the reserve, there is a rumour that Eugene Marais spent some time on the farm that would have then been called Onverwacht. It is further rumoured that a small house which he stayed in which was demolished in the mid-20th century was on this farm. This is in the area in the reserve that we refer to today as Sekgwa Plains. There is a road on the reserve today which we call Eugene Marais and it runs from the west airstrip to Nkonkoni Plains.

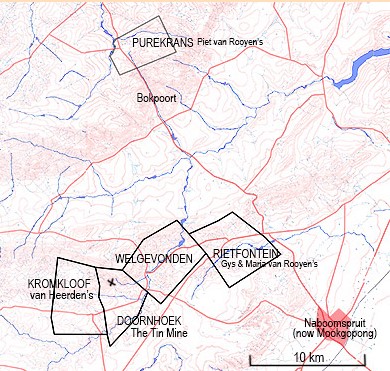

The Welgevonden Game Reserve was named after the farm ‘Welgevonden’, owned by Pienkies du Plessis, who would be the original driving force in the reserve’s establishment. This farm forms part of the reserve today that we would see in the southern plains area. This Welgevonden farm thought to be visited by Eugene Marais is not the one after which the reserve is named [Map 1 and 2].

Throughout South Africa, there are a number of original farms ‘Welgevonden’. The one that Marais was reputed to have spent time on is located next to the farm Doornhoek, as well as the farm Rietfontein. His pioneering studies on baboons and termites he observed on the farms Doornhoek and Rietfontein. These farms are some 70km east and south of the current Welgevonden Game Reserve.

Back To The Chacma Baboon

The name ‘Chacma’ is derived from the Khoikhoi name for this primate species first recorded in 1691. The name the Khoikhoi gave was choa kamma, with its derivation unknown but possibly linked to the barking call given by males as a sign of warning. The name ‘Chacma’ was accepted into the English language around 1820 – 1825 only.

The Bushmen, who believed they themselves were one and part of nature, referred to all other animals as people of some sort. Their reference to themselves and all animals were equal and did not place them above any other animal in nature. They called the baboons ‘the people who sit on their heels’. This describes their sitting posture perfectly and is a clear representation of the intimate observations and respect that the Bushmen had of nature. To them, baboons were just other people with whom they shared the bush.

Chacma Baboons are the largest and most terrestrial monkeys in southern Africa. They have adapted to the more open grassland type savanna environments, heading into the trees to feed on fruit or to escape danger, or to roost. They will also retreat to cliffs aptly climbing up the rocks to escape the nightly predators. I remember a night excursion we did in the Mapungubwe National Park on the border of South Africa, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. We came across a section of the Limpopo River that was flanked on the southern side by 50m high sheer cliffs. There on the rock face were a couple of sub-adult baboons hanging to the side of the cliff on a little ledge, barely big enough to accommodate them. There seemed little chance that they would be caught by any predator or that they would get any sleep either as all their waking energy would have been expired trying to stay on the tiny little platform of safety.

Chacma Baboons are non-territorial and live in large groups known as a troop or flange. The group is looked after by a multi-adult male hierarchy system. The females are outranked by all males. Each female group known as a matriline has attending males. The females are ranked as families and not as individuals. There is great sexual dimorphism in baboons with the much larger males being well equipped with massive canines for troop defense. The sheer presence of large males is enough of a deterrent for any potential predators.

Baboons are often seen in the presence of other animals and will form part of mixed-species groups feeding in a particular area. Impala and baboons often congregate, as a result of food availability but also as a means of protection. The theory of many eyes and ears to detect potential danger in the open savanna environment. Impala however will remain wary of baboons in the lambing season as baboons are known to predate on young impala. As the lambs grow to 2 or 3 months, the threat is perceived to diminish. Impala ewes are not regarded as the world’s best mothers and from the age of six months, lambs are no longer associated with their mothers but do remain in the group along with the other females and lambs, under the watchful eye of the dominant ram. During a severe drought in 2015/2016 in the Kruger region of South Africa, we remember watching adult baboon males hunting the lambs of bushbuck in the dry riverbed below the camp. Although this behaviour is known it is not often that we have witnessed it. The bushbuck mothers desperately finding food would lose concentration and their lambs would be left unattended for too long, giving the baboons time to dash in and grab this tempting meal.

Baboons have a varied diet as would be expected. They feed on the new shoots of trees and plants, seeds, flowers, fruit, and insects making up a large portion of their diet as opportunistic omnivores. They will eat meat including birds and their eggs and are adept at collecting spiders and scorpions as well. Savanna ecosystems are not rich in resources as are forests and so being territorial in this type of environment is not beneficial when searching for food.

Living in large groups overseen by many large, strong, well-equipped males does give satisfactory protection to the troop. The main predator of baboons is the leopard, although baboons are not their favoured prey as many believe. They occupy similar habitat and baboons roost for the night in areas that leopard would occupy when hunting at night. I have also witnessed lions hunting baboons, successfully, which is no mean feat, given a baboon’s agility.

Socialising is extremely important for baboons. Grooming forms a large part of this social interaction between family members and reaffirms rank amongst the males. Late afternoon and early mornings are ideal times for this, and we often observe this ‘family’ time on the reserve. Three troops in particular provide much enjoyment for us. The first troop we encounter come raining out of the fig trees at Fig Tree Plains, eager to get the day started and making a mad dash across open ground for the surrounding hills. The second troop we find in the mornings is along the Taaibos River towards the west, where they have spent their night in the safety of the large waterberry trees that grow in the river line. The third troop is often seen socialising in the late afternoons at Leopard Dam, where they eventually make their way into the waterberry trees that flank the dam and the drainage line down towards Rhino Dam. There are many other groups on the reserve that we observe but these three have become regular sources of entertainment.

So whilst the title of this story may sound like the start of a bad joke, or perhaps a riddle to comprehend the association of such a mixed ensemble, it is simply the coming together of the Chacma Baboon, a poet, and a naturalist. This happened as a result of a broken-hearted man’s journey to the end and his passion to explore and understand the changes in his life and in nature.

The nights are now cooler, the days mild with the sun rising well after 6am. The dark of the night comes sooner as Winter rolls slowly into the reserve. This is a favourite time of year, with the change in colours and scents wafting through the slowly turning syringa trees. We are reminded daily of the tempering of the seasons. Time for a change.

O cold is the slight wind,

and keen.

Bare and bright in dim light

is seen,

as vast as the graces of God,

the veld’s starlit and fire-scarred earth

Translated from the poem ‘Winternag’ by Eugene N. Marais, published 23 June 1905

Text – Neil Davison

Photographs – Neil Davison

Map 1 – Adapted from the Waterberg Bioquest website by Warwick Tarboton

Map 2 – Referenced from the mindat.org website for the Waterberg Region, Mookgopong (Naboomspruit)

References:

- 30 years of personal observations by the author on various Reserves in South Africa including Welgevonden Game Reserve

- The Soul of the Waterberg, Clive Walker & J.P. du Bothma, African Sky Publishers, Houghton, 2005

- ‘The Road to the Waterberg’ by Eugene N. Marais, an essay written on his first adventure into the Waterberg, re-printed and translated in Leon Rousseau’s, The Dark Stream; The story of Eugene Marais,1974

- Pioneers of the Waterberg: A Photographic journey, Elizabeth Hunter, privately published by E. Hunter, 2010

- Beat about the Bush – Mammals, Trevor Carnaby, First Edition, Jacana, Johannesburg, 2007

- The Behaviour Guide to African Mammals, Richard Despard Estes, Russel Friedman Books CC, 1995.

- http://www.waterberg-bioquest.co.za/history.html

- https://www.poemhunter.com/eugene-marais/poems/

- https://www.mindat.org/loc-261177.html