The Night Stalker – The Aardvark

Aardvark Orycteropus afer

It’s a dark, chilly Winter morning and not much is stirring around Makweti Safari Lodge. It’s 2am, and the only sound is of the soft padding of a nocturnal animal moving around the open area close to the waterhole. His long, tubular nose, close to the ground, his long ears pricked, listening intently. We have caught him in the act on our trip camera. A split-second, small, red glow, barely visible from the undergrowth is the only evidence of this animal’s presence.

This was the first of a few images we would capture of this night stalker close to and in camp. Late February 2019, it’s close to 2am and again, this nightly wanderer has been caught on camera moving close to camp, behind chalets 1 and 2.

This is the aardvark.

Ask most people what they know about the aardvark and the usual answer is little or simply “it’s the first word in the English Dictionary”?

This unmistakable mammal with its pig-like snout, long, tubular ears, relatively heavy build with an arched back, thick, muscled tail and stout legs with long, sharp, spade-like claws, is unique and simply unlike any other mammal in the region. It is widespread throughout Southern Africa, and in Sub-Saharan Africa it is widespread outside of the equatorial forest regions.

The aardvark is heavier in hind quarters than the fore. They have very thick, tapering tails and unusually heavy, powerful limbs. The body is covered in pale hairs, with the hair on the end of the tail and on the limbs being darker. Males in general are darker than females, particularly on the head. They are often colour-stained from the soil in the area they live. Those living in areas where the soil is redder, tend to be stained a brown-red colour. The nose is a muscular tube with incredible movement. The nostrils are densely covered with a mat of hair, which closes the nostrils in, and act as a dust filter. Below and above the eyes are lines of bristles and lower down on the side of the head, tufts of these sensory bristles are evident. These alert the animal to obstructions when burrowing and foraging and protect the eyes from damage. They have excellent hearing and smelling senses with relatively poor eyesight.

Males and females are alike and differences in size are not noticeable. In a study conducted in Zimbabwe in the 1980’s, the masses of males and females ranged between 53 and 51 kgs respectively. There are few birth records, but females will give birth to single young, weighing about 2kg. The gestation period is around 7 months. The young aardvark will follow the mother after a period of +3 weeks in the burrow. The juveniles will dig for themselves at 6 months.

Formicid ants form the large part of their diet, which also includes termites. They locate their food by scent and will then spend time digging into the nest with their large claws, often in several searching spots, eating as many ants possible using a long, sticky tongue. The tongue appears impervious to bites from their prey. Termites, when having had their nests broken into will deploy their “soldiers” who have large bulbous heads and a fair size pair of biting mouth parts. The acid substance stored in the termite head acts to deter the aardvark, who will then move on to locate a different site, failing which it would most likely destroy an entire colony. The aardvark has teeth, but little is understood as to why, as they do not masticate or chew their insect food. The long ribbon-like tongues and large salivary glands allow the food to be deposited close to the stomach. The breakdown process is facilitated in the aardvark by the presence of a muscular pyloric area, which acts much like a gizzard found in birds, where it grinds up the aardvarks food mixed in with the sand and soil taken in during feeding. In drier areas, aardvark will feed on wild melons or wild cucumbers. This will supplement their moisture intake. Feeding on these types of fruit, will warrant the need for their teeth.

Relatively shy, almost strictly nocturnal mammals, they are seldom seen in the day and although common and widespread, remain mostly unnoticed except for the evidence of their nightly foraging activities. Heading out on morning drives we often come across their evidence of foraging from the previous night. Usually active from 9pm until early morning, where they will retire to their burrows to rest out during the day. Although a solitary species, the females are sometimes seen with single young, digging deeper burrows to protect them and their offspring. Males will often dig shallow burrows in which they will rest during the day. Newly dug occupied holes often have small flies around the opening of the hole. Activity in summer is strictly nocturnal, where the animals forage for formicid ants and termites. In Winter, feeding activity starts earlier and sometimes begins in the late afternoon as termites and ants go deeper in their colonies or nests during the colder parts of the winter nights.

Their front feet have four digits, with the hind feet having 5. Tracks of these animals clearly show 3 of the 4 front digits in the front foot track and 3 sometimes 4 in the hind foot track. The front feet end in large claws with sharp edges.

In the photograph I took of the tracks found on an early morning drive (below), 3 digits of the back left foot are clear (marked 1-3) with the 4th only just visible as a small depression (marked 4). The long arrow indicates the direction the animal was moving. The yellow arrow in this image shows 2 clear claw marks from the front foot, although the rest of the track is not clear, as the hind foot often overlays where the front foot was placed.

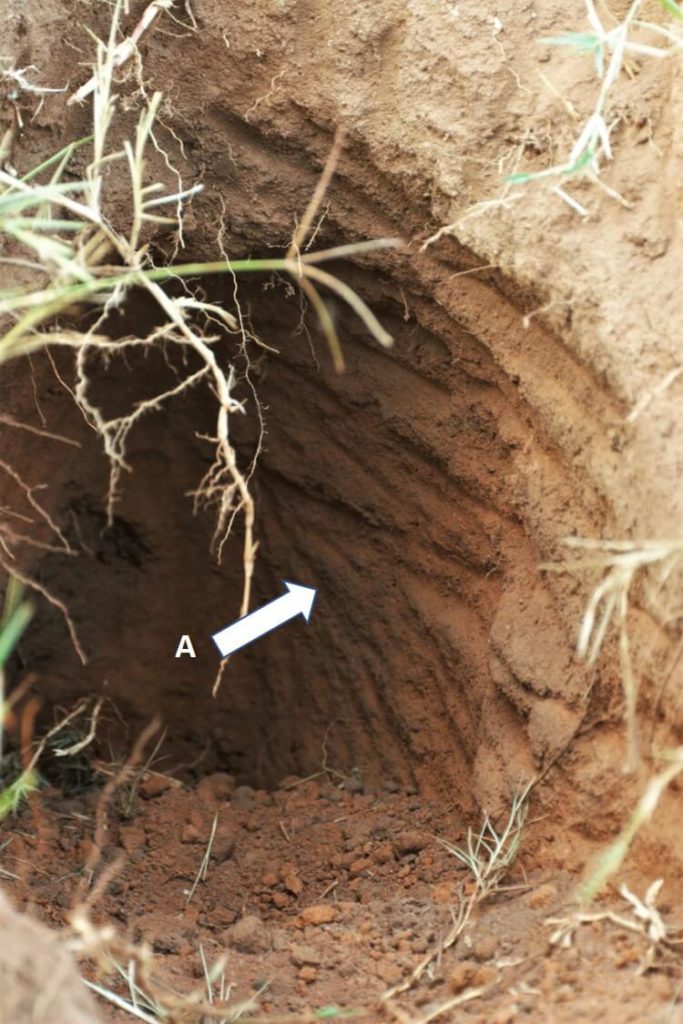

The photograph marked A (below), shows how well they are adapted to digging and shows how sharp their claws are, with the claw marks evident on the sides of the wall.

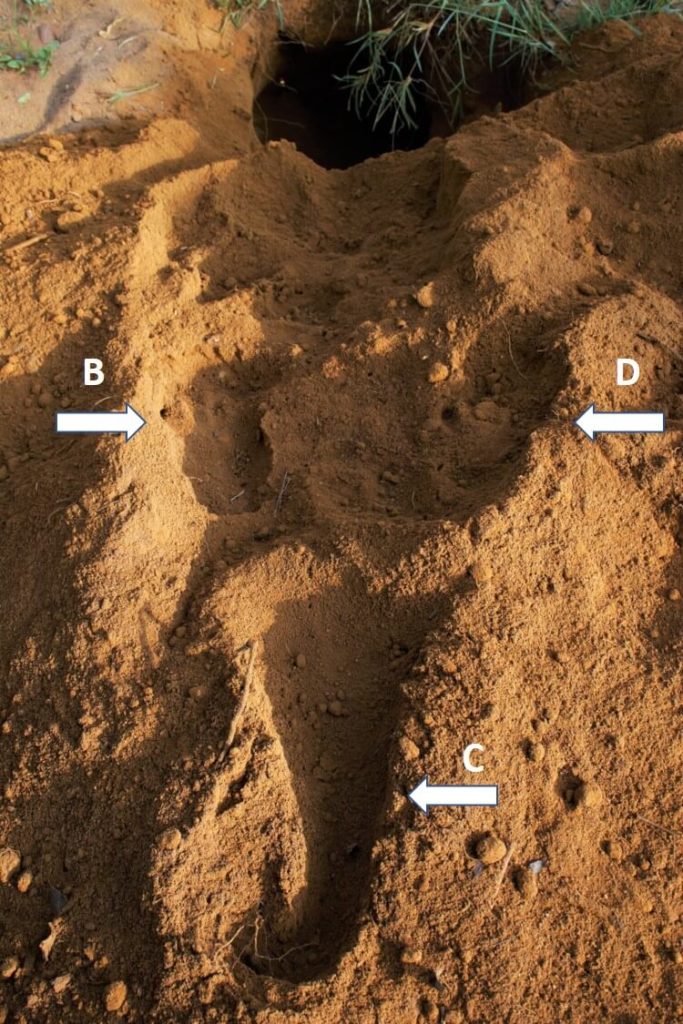

Aardvark appear to have 3 kinds of excavations, apart from the small exploratory diggings. The image with all the arrows shows various exploratory diggings in a small area.

The first excavation type are shallow diggings, deep enough to access the nest of their food. Usually in flat ground they can be deep enough for the head and shoulders of the animal to be covered, only sometimes deep enough to submerge the entire animal. These holes are not used for refuge and are not revisited.

The second type are dug ‘overnight’ and serve as temporary refuge holes. Usually dug by males, they are a couple of meters deep and are quite shallow. They may be used over a period of a day or 2 and sporadically revisited. They have a chamber at the end of the tunnel to allow the animal to turn around.

The third type of digging is a permanent burrow dug for the young to be born in. These burrows are dug quite deep, have extensive burrow systems and chambers and several entrances. The females utilise these burrows more, where the males are more nomadic within their home ranges and will tend to rest in burrows dug as described in the second type.

I particularly like the image I took where the hind feet and tail marks are clear in the sand excavated from the burrow (below). The hind feet (marked B and D) and the tail (marked C) are clear in the print this aardvark left at a burrow site near Andres Pan on the reserve. When the aardvark walks, it walks on its toes however when they pause, they will sink onto their haunches, as in this case showing the feet and tail prints clearly. When entering their holes, they do so head first as is evident in this image too.

Abandoned aardvark burrows are utilised by a variety of other species for shelter. Warthog, porcupine, honey badgers, reptiles and insects will use these open spaces. In the Kalahari where trees are in short supply, leopard have been known to use old aardvark holes to take shelter too. The little bee-eater has been recorded to nest in the ceilings of abandoned aardvark holes, burrowing their tunnel nests into the ground. I witnessed this on an afternoon drive late last year when we stopped for a break close to Sterkstroom Pan. A pair of little bee-eaters was flying in and out of this old aardvark hole and after a while stopped coming out. It was evident that they would spend the night in there. Having read about this behaviour before, I was pleased to have witnessed this first hand.

Photographs – Neil Davison

Text – Neil Davison

References:

- Personal observations by the author on Welgevonden Game Reserve and other Reserves in Southern Africa

- Mammals of the Southern African Sub Region, J.D Skinner & R.H.N. Smithers, Second Edition, University of Pretoria: Mammal Research Institute, Pretoria, 1990

- Smithers Mammals of Southern Africa: A Field Guide, R.H.N Smithers, Third Edition, Southern Book Publishers, Johannesburg, 1996

- Field Guide to Mammals of Southern Africa, Chris & Tilde Stuart, Fourth Edition, Struik Nature, Cape Town, 2007

- Beat about the Bush – Mammals, Trevor Carnaby, First Edition, Jacana, Johannesburg, 2007