Black and White

Nature does not operate in grey areas. There can be no question that systems in nature are clearly defined with opposing principles appearing quite clearly in black and white. The areas in between are just as clearly defined and the infinite links that exist between everything, have just as well-defined purposes as the next, and in their own right are exactly that, either black or white.

We tend to forget from time to time, that what we get the pleasure of witnessing every day, are the species and systems, behaviours and traits that are the surviving best of the best. Those we don’t see, have been lost or have become so rare or simply could not make it. Those we would regard as the grey areas as such, are the ones that did not make it. We live our own lives, constantly adapting and changing not to survive anymore but to stay in touch with the demands of modern life. Our choices are based on likes, influencers, and emotion. We create so many grey areas around our own existence, we forget to, or we chose not to live with conviction.

Because what we observe in nature is fairly ‘constant’, with so much going undetected, when we see something that is unusual it immediately sparks a renewed interest.

Drifting down into the northern parts of the reserve is always a treat. We leave some areas to explore now and then, enhancing the element of surprise in venturing into unfamiliar, familiar territory. Early April, the mornings are cool, the sun rises slower and the light that catches the tops of the trees, lingers a while before spreading down into the open plains. We are heading to an iconic fig tree at Nyala plains for a long-anticipated coffee stop. We have spent the better part of the morning looking for lions that have managed to slink away undetected from us into a large block of seringa and silver cluster leaf trees. As we inch towards a cup of fresh brewed coffee with home-baked rusks, we spot an unusual pair of Gabar Goshawks at the top of a small umbrella thorn. Catching that golden light caressing the treetops, there sat these little raptors as clear as day, in black and white.

What immediately struck me was that the lighter, ‘normal’ coloured one had caught something, that something being the dark, melanistic one. As we neared their sunning spot, it was clear that we were looking at two distinctly different individuals that are exactly the same. When I first started guiding full time, professionally, the reserve on which I was based had an abundance of Gabar Goshawks that were of the darker morph. I remember clearly thinking that this was the norm and that the dark side of this species was quite common. It would appear that this was just the case for this area. For the dark morph to be prevalent, the prevalence of the recessive gene that causes the increase in melanin in the birds’ feathers must have been attributed to the parent population. Light or normal coloured birds carry this recessive gene but the expression of this is reduced by the prevalence of the more dominant genes that produce the light morph. None the less, this was a special and unique sighting and my first for Welgevonden Game Reserve. On returning to the Camp, I contacted a much more knowledgeable mind on these things, renowned professional birder and author, Warwick Tarboton.

Mr. Tarboton needs little introduction as he is a well-respected, ornithologist, photographer and scientific mind who has contributed so much to the scientific community in southern Africa and elsewhere on damselflies, dragonflies and more particularly birds. My questions to him were around the prevalence of the melanistic morph of Gabar Goshawk in the Waterberg and the effect that the darker colour may have on the breeding success of these birds. Basically, I was interested to know if the normal coloured Goshawks could see through the dark veil the melanistic morph birds were draped in, to see the soul of the bird behind it. And so, I asked:

- Is it quite common that either morphs will interbreed and or associate with each other?

- Do they still recognise as individual from a different colour morph as a potential mate?

- What impact does the colour change have on breeding success? If any?

As always, I was grateful for the speedy response.

Hi Neil,

Thanks for the e-mail and the nice pic of the goshawks. Long ago in Kruger Park a survey of the Gabars revealed that about 10% of the population was melanistic; I think it is higher than this in Namibia but perhaps lower here in the Waterberg, and perhaps it varies over time in response to climate or some such factor. Either way we do find melanistic birds here and there.

It doesn’t seem that melanism impacts their pairing or behaviour in any way and mixed colour pairs often have mixed colour offspring. I think that vocalisations and displays are the most significant thing for pairing, hence colour seems to be irrelevant.

Regards,

Warwick

This is interesting. Even when nature throws a spanner in the works, it would appear that the underlying systems remain in place and even when things appear as ‘black or white’ they stay true to the origins. It would be interesting to know exactly what the normal coloured Goshawks see, as we know birds see particularly well in colour, and that this has no impact or minimal evidence of any impact in mate choice. Social information is a more effective way of assessing resources. This is inspiring.

Back to Black

Melanism is not unusual, just not that common. There are a number of animals from birds to insects, reptiles and mammals that have the rarer dark morphs express themselves from time to time. At first, they were believed to be different species altogether but with the progression of science and through greater understanding and appreciation we have learnt that the darker forms are the same species with a varied colour palette.

Melanism is generally defined as an increase of dark pigment in the plumage, resulting in a blackish appearance. Furthermore, melanism is often associated with mutations of one gene that encodes the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), a protein involved in regulating melanin pigmentation (van Grouw, 2017).

The main pigments in birds that express colour in their plumage are melanins and carotenoids. In birds, the melanin cells, consist of eumelanin which is responsible for colours that are black, grey and / or dark brown in feathers, whereas phaeomelanin is responsible for warm reddish brown to pale buff colours. The melanin cells cannot produce both types of colours at the same time and switch to either one or the other. This switch mechanism is controlled genetically. Apart from providing bird feathers with an array of colours, the melanin grains provide function to them as well. The different shades of colour denote varying concentrations of these cells.

Because of the rod like shape of the eumelanin grains in the feathers, they add structure and strength to the feathers. It is noticeable that the wing tips of many birds are darker where there is likely to be more stress on the feathers in flight. In addition, this reduces wear and tear and bacterial degradation. Even in almost all white birds, the wing tips are darker. In some instances, melanism can be disadvantageous in that in some animals it impacts mate recognition, thereby reducing reproductive success, although not believed to be relevant in birds. Other disadvantages include the reduced ability of the animal to synthesize Vitamin D from the sun.

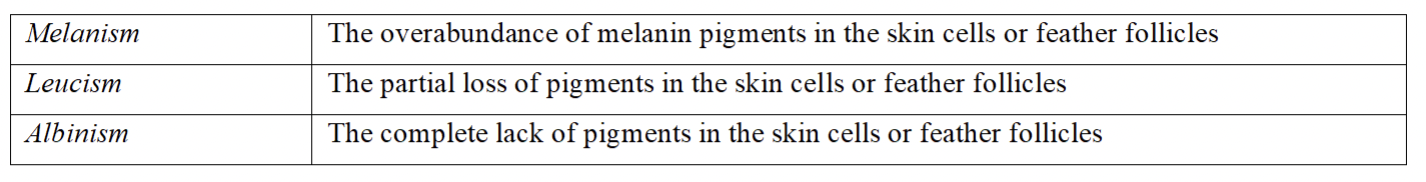

Melanism vs. Albinism vs. Leucism

Because Albinism is the complete lack of pigment, the eyes of these animals often appear red, where the lack of pigment in the iris of the eyes, allows the red colour from the blood vessels in the eyes to come through.

In February 2019, it was reported in northern Kenya that a black leopard had been spotted. This was and is a rare sighting. Often referred to as a ‘Black Panther’ this term is misleading and also misused. Jaguars of South America also from time to time express the melanistic form and are called Black Panthers. This term is however used generically for any dark or black form of spotted cat. In the case of the Leopard spotted in Kenya, it would be better referred to as a black Leopard, just a dark variation of the traditional more common coloured Leopard.

This black leopard was sighted in the Laikipia Wilderness Camp area and although rare is not unusual. Black leopards have been sighted in India before, with the last African sighting being reported over one hundred years ago. Probably more usual than recorded, this sighting was made more sensational by some great high-quality images that were captured. This was a first, and so made it more striking as a rare event. Just because we don’t see them, does not necessarily make them rare. Rare as a sighting, not rare as an occurrence, but no less special.

Birds in particular show degrees of polymorphism or colour variation that is influenced by population, geographic location, or other environmental factors as stated by Warwick Tarboton. Melanism or dark morphs are one form of colour variation as it would appear. According to Faansie Peacock, about 3.5% of all bird species have a colour morph. Peacock further states that Gabar Goshawks have a higher prevalence of melanism than other bird species which also show melanistic versions. The Swaziland population has higher degree of polymorphism than the rest of southern Africa with nearly one in four birds turning out dark.

This melanistic Gabar Goshawk is quite different in appearance to the one we spotted at Nyala plain that winter morning. It is most likely a juvenile as it does not express the colour in the beak and legs that the adult melanistic birds do. The eye is also red and not as dark as the adult bird. In comparison the lighter or normal coloured juvenile shows all the characteristics that one would see with the usual amount of melanin in the colour palette.

Interestingly both these birds were seen on a Reserve south of the Waterberg about 160km from Welgevonden Game Reserve. These opportunistic sightings one month apart and within completely different locations and habitats were fantastic and having not seen the dark side of these birds for the past 20 years, they are a wonderful reminder of the great diversity within the greater diversity of life around us.

Text – Neil Davison

Photographs – Neil Davison

References:

- 30 years of personal observations by the author on various Reserves in South Africa including Welgevonden Game Reserve

- Trevor Carnaby, Beat about the Bush – Birds, 2007, First Edition, Jacana, Johannesburg

- G.L. Maclean, Ornithology for Africa, 1997, University of KwaZulu Natal Press, Scotsville

- Roberts Birds of Southern Africa 7th Edition; PAR Hockey, WRJ Dean & PG Ryan, John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Jacana Publishers, 2005

- Rob Little,Percy Fitzpatrick Institute, UCT, ‘Colour Coding’, African Birdlife, July/August, 2014

- Hein van Grouw, The dark side of birds: melanism—facts and fiction, Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club, 37(1):12-36, British Ornithologists’ Club, 2017 https://doi.org/10.25226/bboc.v137i1.2017.a9 http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.25226/bboc.v137i1.2017.a9 7. https://faansiepeacock.com/grey-is-the-new-black/